“The meaning of life, for all animals, is a life of freedom.” -A.D. Williams

When we see an ill or injured fox, we are quick to assume that this animal should be trapped and taken to a vet. However, this is not always in the animal’s best interest.

If you have a companion animal, you will know that every trip to the vet is stressful for them. That stress is magnified 1000-fold for a wild animal that has never before been handled by humans or been kept captive in a confined space. To a wild fox it is hugely traumatic to be captured and handled by humans. It is the equivalent to us being abducted by an alien. The shock of being trapped may result in a physical shock and can in extreme cases even lead to death.

From our human perspective we tend to glorify a life in captivity – the fox is warm, well fed and sheltered – what’s not to like? But for a wild animal that is accustomed to a life of independence and freedom, life in captivity can be torture. Foxes are used to roam around their home-range to scent mark their territory. During mating season, they travel far and wide in search of a mate and once the cubs are born, rearing them is a family affair with mum and dad as well as other family members being roped in as helpers rearing the dependent offspring.

I have been advised by rehabbers that have an enclosure in their garden as well as from a rescue centre that runs a CCTV camera system over the night when foxes are most active, how much most foxes struggle with captivity. They scratch the walls, chew the wooden structures and mesh, jump up and down to find a way out and bark loudly. They are restless, bored and frustrated.

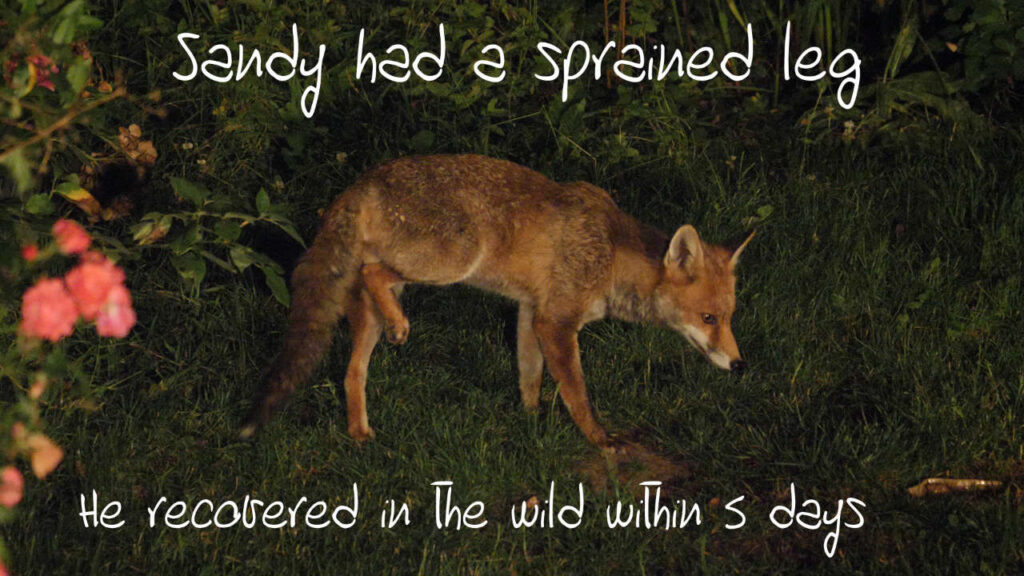

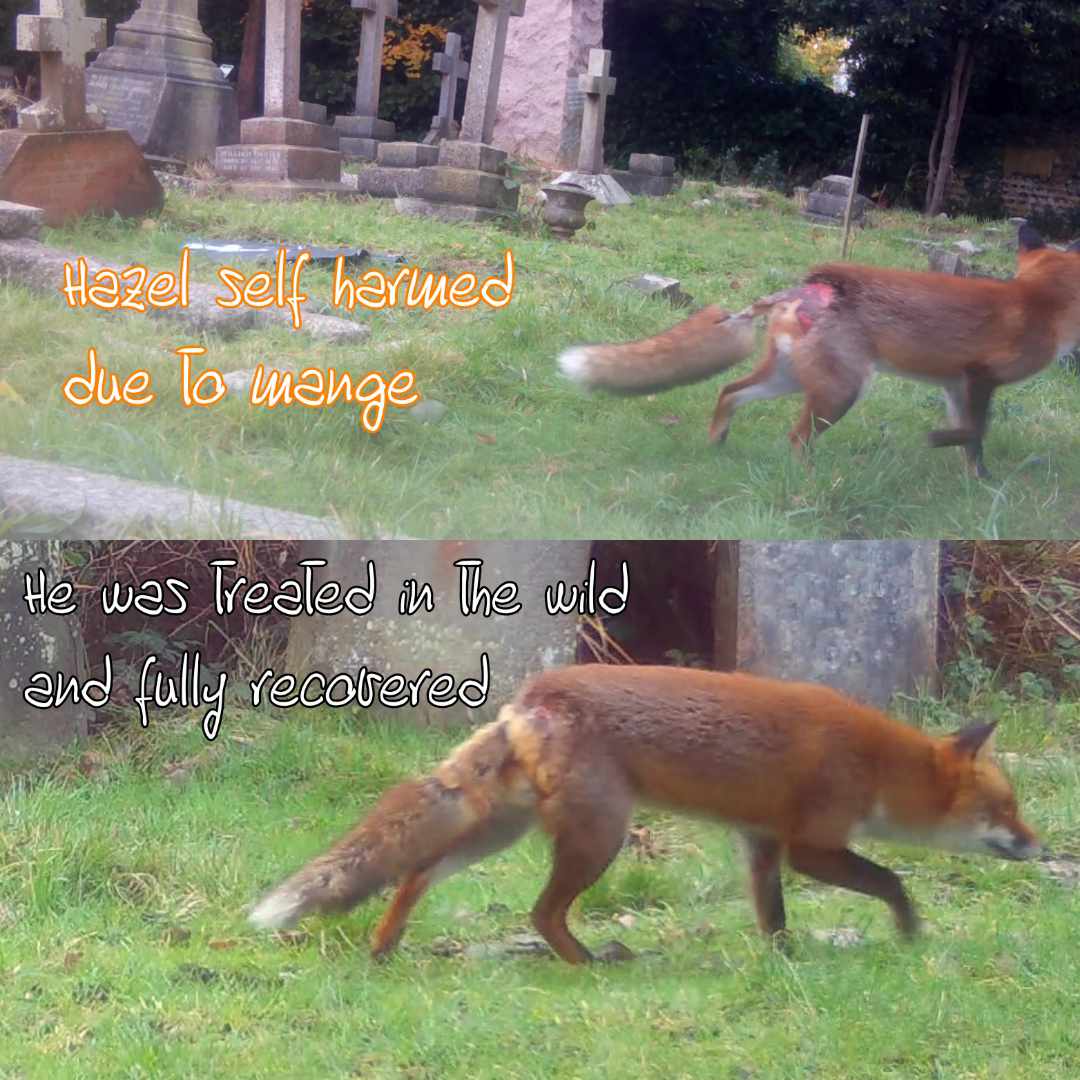

Foxes frequently get ill or injured. Mange is common especially at the end of summer when vixens are depleted from rearing their cubs. Mange will be deadly if left untreated. Leg sprains happen often when foxes jump over obstacles or get caught up in quarrels. Breaks are also common and scientific research found that 80% of foxes over 4 have historic breaks that re-set and the foxes adapt to the handicap of being lame. During mating season foxes often get bite wounds on their face or paws. Puncture wounds and lacerations from territorial quarrels often heal by themselves. But sometimes they may get infected which can lead to sepsis and possibly death if left untreated.

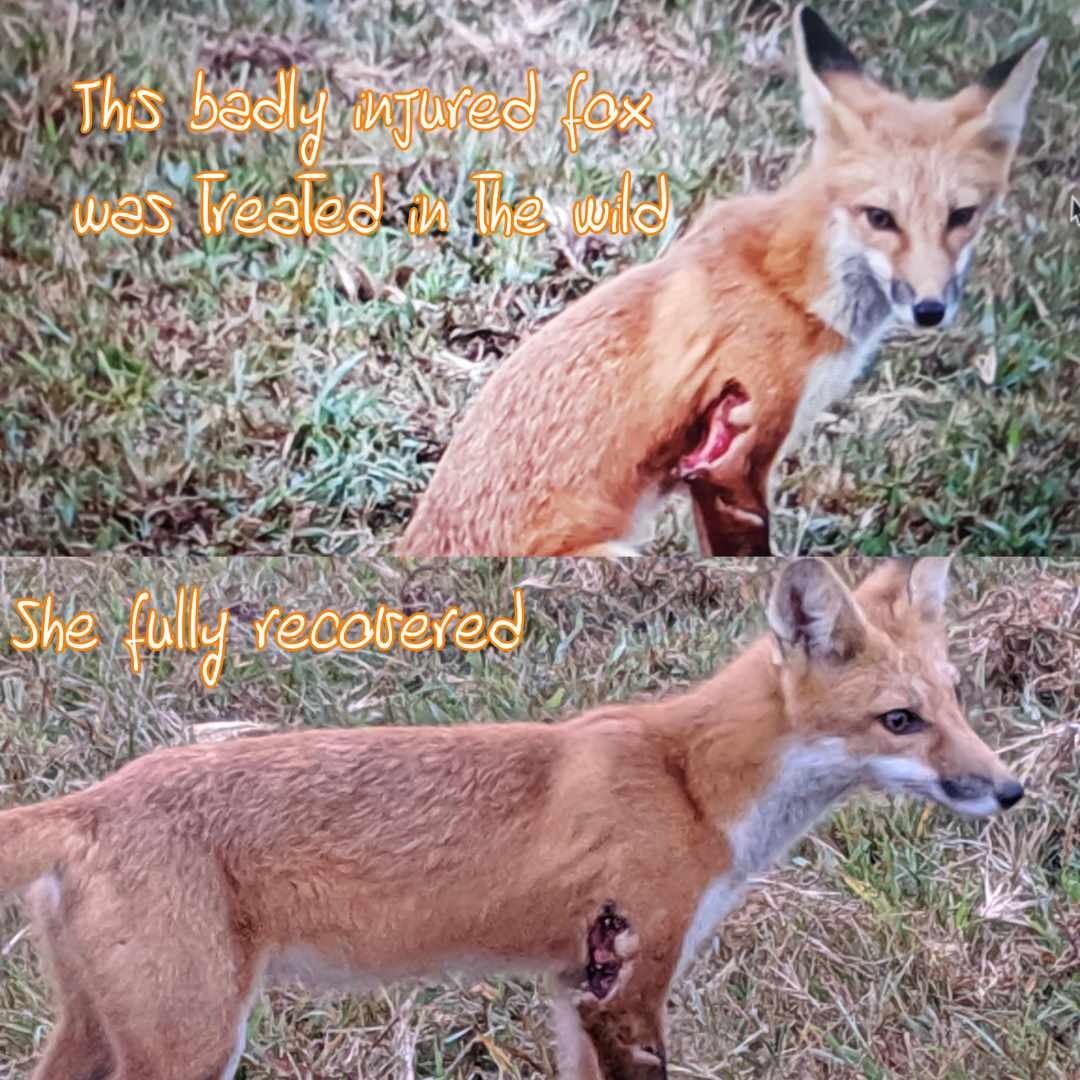

If we can help and animal to recover from illness or injury in the wild by supporting them with supplementary feeding as well as (in some cases) giving them target-fed medication responsibly, I believe this is always worth trying. There is no trauma of trapping, no stress of life in captivity, nor the potential loss of the territory for the fox. Supplementary feeding in the wild allows the fox to rest up and heal whilst they remain connected to their skulk and territory. Of course, treating in the wild is easier said than done as it is very difficult to get prescription-only meds for a fox in need and it will require much dedication, patience and tenacity by the fox’s guardian to nurse a fox back to health in the wild where their movements can’t be controlled.

Once a fox has been trapped and handed over to the vet, they have entered the system and become “property” of the treating vet. By law vets and rescue centres are not supposed not to re-release ill or injured wildlife ‘that may be at a disadvantage’ back into the wild. Different vets and rescuers interpret this rule in their own way.

If a fox that has adapted to live with a handicap (such as a re-set break, a missing eye or lolling tongue) is trapped, a vet may choose to put this fox down, even though they coped well living in the wild as their handicap can be interpreted as a “disadvantage”.

Some rescuers that are treating a fox for mange in captivity, may choose not to re-release the fox until a full coat has regrown as not having the insulation of a full coat may disadvantage the fox. It can take months for a full coat to regrow. Months in captivity will most likely result in the fox losing their territory and becoming dependent on being fed. Therefore, this fox will be disadvantaged compared to other wild foxes and this will potentially result in the rescued fox never being re-released but having to spend the rest of their life in captivity.

Every fox is different and needs to be assessed as stand-alone case. What you hope to achieve in wildlife rescue is the ‘goldilocks formula’ which means to trap a sick fox was the right decision. The best- case scenario is to capture a fox that may just need a ‘quick fix’, such as having an infected abscess drained and given a long-lasting shot of antibiotics that will support their healing process before a swift re-release into the wild. A definite case for trapping would be or a badly injured fox with injuries that are not survivable such as a broken back, or a snared fox like Lucky that had the illegal hand-made wire snare growing into his neck flesh, progressively suffocating him.

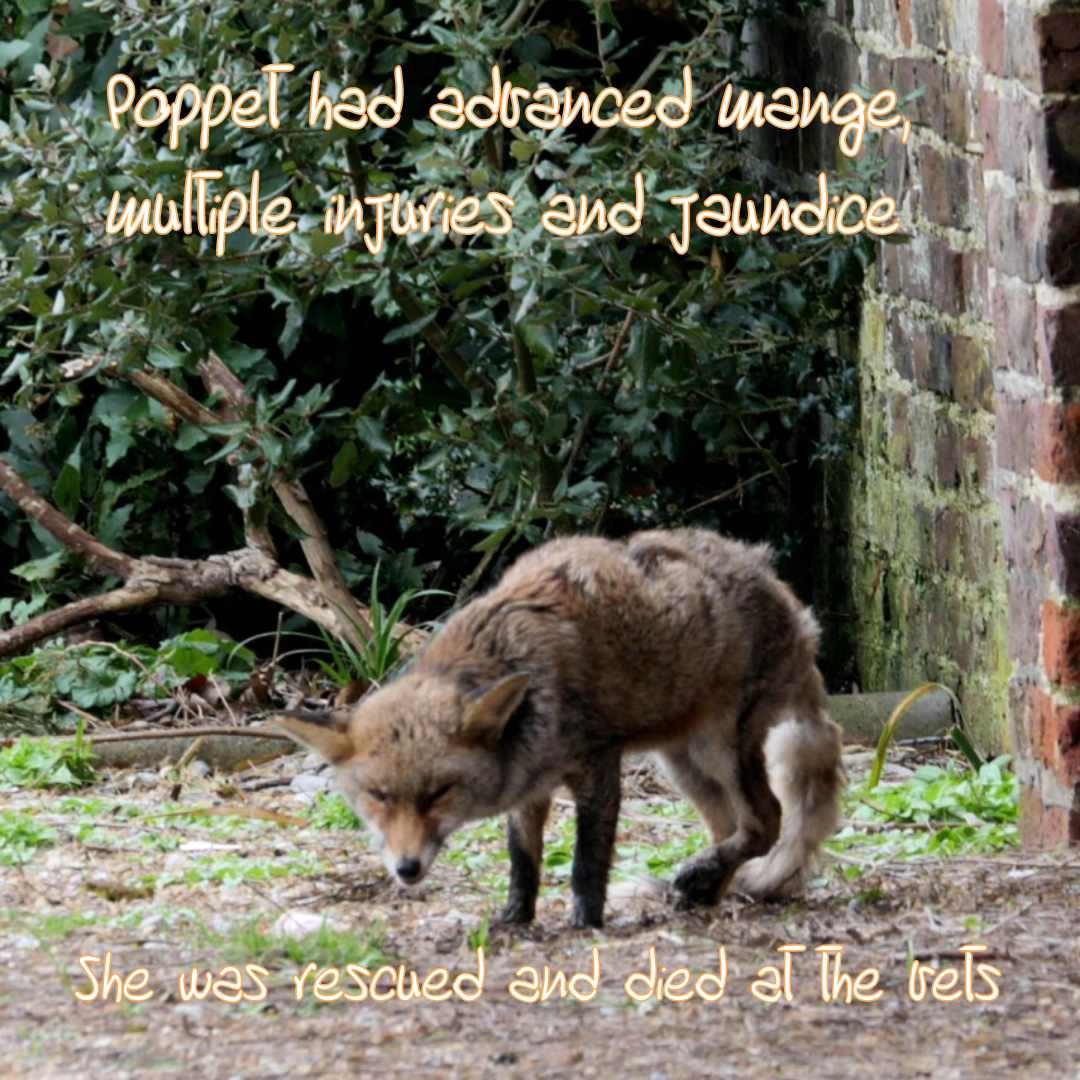

Another case for trapping is a fox that may already be dying from organ failure and/or sepsis and that would suffer a great deal more dying a “natural” death in the wild, rather than being euthanized. Poppet, a little frail vixen I recently rescued falls into this category. Wildlife rescue can be an ethical minefield and you may become emotionally challenged to the extreme.

When I rescued Poppet, who was suffering from advanced mange, a severe leg injury, extreme malnutrition and jaundice, I knew that if she was to survive, she would have to stay for a few weeks in ‘rehab’. My local animal rescue in Worthing has no wildlife kennels. The Fox Project in Kent does only take foxes from their local catchment area that West Sussex is not part. So, I contacted Brent Lodge Wildlife Hospital that recently completed the build of brand-new wildlife kennels. But there are currently only 4 kennels. 3 were already occupied by other fox patients and the ward manager said to me: “We can admit your fox, but if we take her in, we will not be able to take any orphaned cubs in” – What a conundrum! Who is ‘more worthy’ to get a chance of survival – the vixen that had zero support from humans whilst she became progressively more ill, or a possibly orphaned or injured cub?! How do you solve this ethical conundrum? I think being in the moment is key – Poppet needed help right here, right now. A kennel was available, so why not give it to her? But sadly, Poppet died overnight at the vet and never made it into rehab. She was a lot worse than assumed and was suffering from jaundice on top of her other conditions. I still feel she was “rescued” as she had been given hydration, food and pain management and was in a warm, dry place. She died peacefully in her sleep. I think her death might have been more drawn out and painful if she had eventually died a ‘natural death’ in the wild, so in her case it was the right thing to do to get her off the streets.

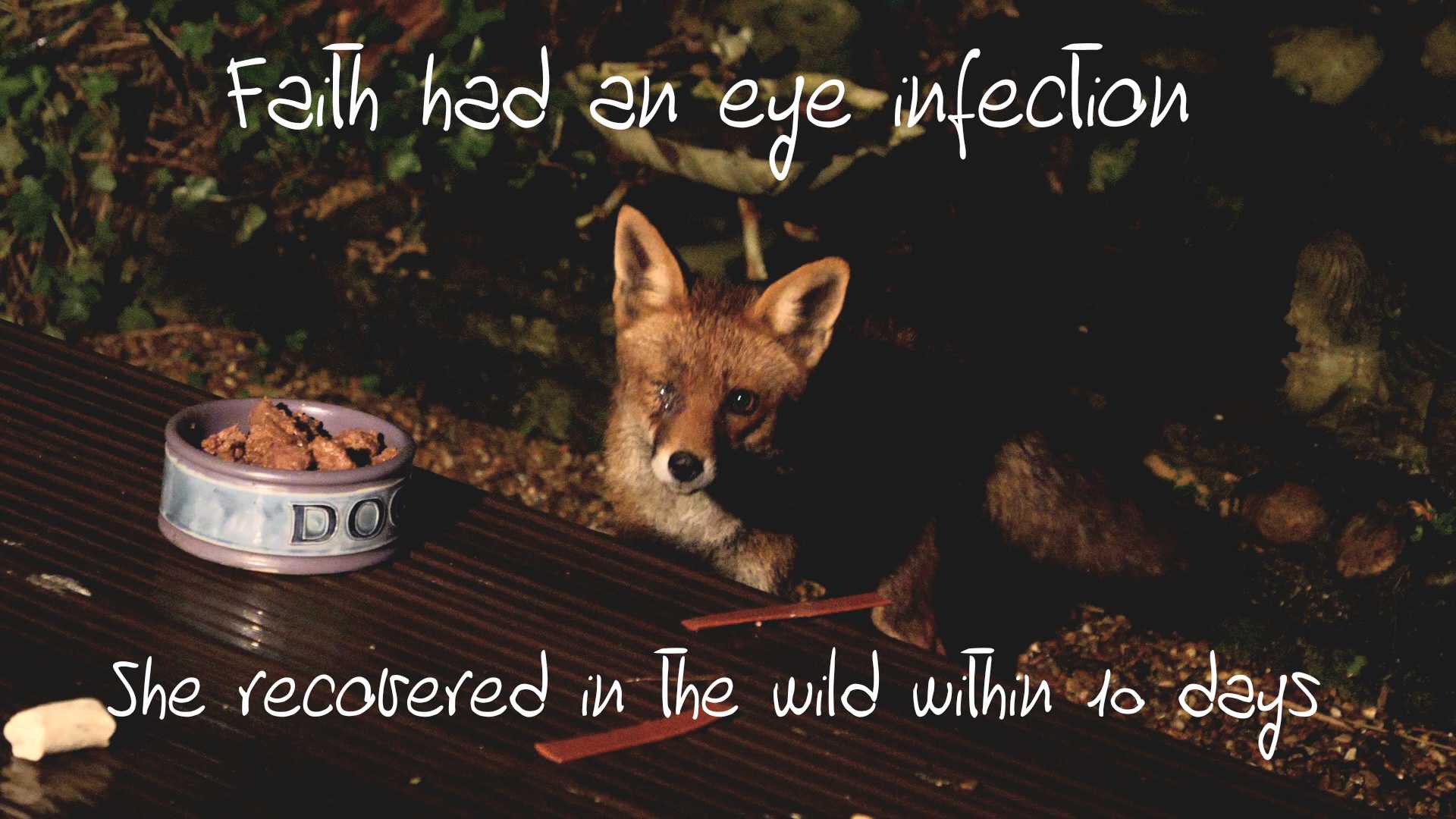

Foxes often surprise me – sometimes seemingly hopeless patients bounce back with minimal support in the wild. There are many cases where it is not possible to trap – maybe no rescue organisation operates in an area or if there is one, they have run out of traps? Maybe the ill fox is only seen on public land like a park where no trap can be set? Or a trap has been set the fox is just too neophobe and cautious to go inside? In these cases, it is our duty to not turn the other way but to support the fox any way we can with food and water, by providing a shelter and trying to get the treatment they may need from a vet who may be willing to save a precious wild life beyond the red tape.

I have seen foxes with terrible open wounds that looked not survivable make a full recovery in the wild just by being fed and given a course of anti-biotics and anti-inflammatory treatment. I have witnessed foxes that were severely malnourished and completely naked as a result from sarcoptic mange bounce back within a month of receiving just one dosage of Bravecto and plenty of food in the wild. Foxes are resilient, tough little warriors that can heal even if all seems lost.

Until sometimes all is lost and a fox may die even with the best of support given in the wild or in a rehab facility. Sometimes it is kinder to let them go or help them to die but until then, it is our duty for fight for every single precious wild life! To sum up: Trapping makes sense for an animal that has no chance of recovering in the wild and may need to be euthanized to shorten their suffering. The key is to treat each animal as an individual case to decide if the stress of tapping a fox will be offset by the life-saving treatment they could receive.

The 10 potential reasons that speak against capture are:

- Foxes are wild animals and much more resilient than our companion animals. If they are well fed and have a strong immune system that have a good capacity to heal without any intervention

- Foxes are neophobe and it therefore can take weeks to trap a fox. Sometimes it is just quicker and more efficient to treat in the wild.

- It is extremely stressful for a wild animal to be trapped, handled by humans and live in captivity and this can be detrimental to their health. In extreme cases the shock of being captured my lead to death of the fox.

- In spring foxes rear young. If you trap a parent or ‘helper fox’, this may condemn the dependent cubs to almost certain death.

- Be cautious when capturing seemingly “abandoned” fox cubs. Often mum is nearby and regularly visiting the cubs to nurse them. Sometimes mum is doing a den move and will relocate cubs one by one. Observe and get expert advice before interfering.

- Not all vets are wildlife-friendly and some are all too quick to “euthanize” a fox that could recover with time in rehab or some support in the wild.

- Injured foxes often need after-care in rehab. However, “beds” in rehab are usually very limited, so sometimes foxes are being put down simply because there is no kennel available for them. This is especially true during summer when rescue centres tend to be full to the brim with orphaned cubs.

- If a fox is kept longer than 3 weeks in captivity, they will very likely have lost their territory and also become too dependent on humans to be re-released safely back into the wild. This may condemn them to a life-time in captivity.

- Sometimes re-released foxes may struggle to claim their old territory and to be accepted by their skulk. They may become displaced, itinerant foxes, struggling to survive.

- The term “wildlife rescue” is not protected. There are cowboys operating in the field who hoard animals and keep wild foxes forever in captivity as pets in tiny sheds. So, make sure the wildlife rescuers you contact are a legit organisation with a good reputation.

What To Do If ‘Your’ local fox is ill or injured

If you support a local fox and they become ill or injured, I advise to monitor them daily, ideally using binoculars. Take photographs or film footage that you can share with your local vet or rescuers. You can find your local wildlife rescue here: https://www.helpwildlife.co.uk/. Make notes of the foxes visiting times and if you have not done so already, set up a feeding pattern as food will be used as bait in a trap or a carrier for medication. You know this animal best, if you feel that they are very unwell, trust your gut and get help. Contact multiple rescuers and vets as chances to get more than one opinion and to give the fox the best chance of survival. If the fox is in a very bad way and needs rescuing, stay with the animal until the rescuer arrives as many rescue organisations won’t come out if the animal may have disappeared as it would be a wasted trip for them. Equally make a case for this fox if a vet wants to write them off and you know you are able to support this fox in the wild to increase their survival chances.